The owners of a Bundaberg Region farm have worked with the South Sea Islander community to commemorate a gravesite more than a century old.

In July last year, Mayor Jack Dempsey issued an historic apology for the past practice of “blackbirding”, that saw indentured South Sea Islander labour forced to work in the region’s cane fields.

Around 62,000 people were tricked or forcibly removed from the Pacific Islands between the 1860s and early 1900s and were subjected to inhumane treatment as they harvested cane and cleared rocks from fields.

There are reminders of this history throughout the region, from the Basin swimming hole in Bargara to the stone walls that line farm boundaries.

But some of the history is not so easily seen.

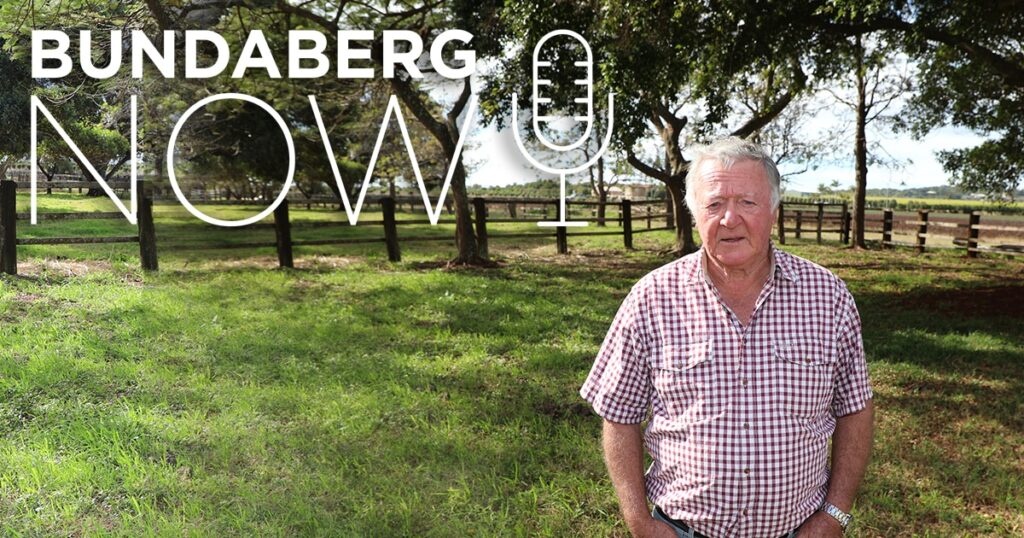

In 2013, Brian Courtice heritage listed a South Sea Islander gravesite on his property, Sunnyside, a farm on Windermere Road that’s been in his family for almost 100 years.

“When my grandfather and Ben bought Sunnyside, some of the neighbours told them that there was a graveyard because they used to bring cane through this property to the juice mill that fronts Windermere Road and they’d see freshly dug graves,” he said.

“I always knew where the graves were, but I was not able to heritage list the gravesite because I couldn’t prove it.

“But finally, after several failed attempts, I hit on the idea of getting ground penetrating radar and Gayle Read who then worked for the Council at the cemetery to bring it out.

“She was able to substantiate the fact that 29 South Sea Islanders, one at least of whom is a child because of the size of the grave, are buried here.”

Third generation South Sea Islander and local Bundaberg man Matthew Nagas said he was thankful for Brian’s commitment in finding out more about the history of his property.

“Brian’s discovery was confirmation of what, what we had been saying for years that our people weren’t taken to cemeteries, they were buried in the cane fields where they died,” he said.

“It was a confirmation from the stories that we passed down to our families and what’s been happening.”

He said the site was a place for the community to reflect and pay respects.

“We feel a lot of peacefulness, tranquility,” Matthew said.

“Brian does look after that particular area now, he doesn’t let any farming on it or that sort of thing, you know. And so we’re very thankful for that.”

Listen now to hear more :

In this series we shine a spotlight on the heritage buildings and infrastructure in our region.

Listen as we uncover memories, mysterious ghost stories and bizarre facts about some of our most iconic structures.

You can also listen on Google, Apple, Spotify, TuneIn or your favourite podcast app.

Hidden Histories: South Sea Islander transcript:

Gennavieve Lyons [00:00:06] Welcome to this special series of the Bundaberg Now podcast where we shine a spotlight on the history of our region.

My name’s Gennavieve Lyons and I’ll be your host as we uncover hidden histories and unknown stories about our historic structures and areas in the region.

In July last year, Mayor Jack Dempsey issued an historic apology for the past practice of “blackbirding”, that saw indentured South Sea Islander labour forced to work in the region’s cane fields.

Around 62,000 people were tricked or forcibly removed from the Pacific Islands between the 1860s and early 1900s and were subjected to inhumane treatment as they harvested cane and cleared rocks from fields.

There are reminders of this history throughout the region, from the Basin swimming hole in Bargara to the stone walls that line farm boundaries.

But some of the history is not so easily seen.

In 2013, Brian Courtice heritage listed a South Sea Islander gravesite on his property, a farm on Windermere Road that’s been in his family for almost 100 years.

Named Sunnyside, the farm has a dark past that Brian is helping to shed light on.

In this episode we hear from Brian about his work to identify and protect the graves, and third generation South Sea Islander Matt Nagas about respecting the past and acknowledging the legacy of those people.

Adele Bennett [00:01:37] I’m here with Brian Courtice, thanks so much for showing me around your farm. Could you tell me a little bit about the property?

Brian Courtice [00:01:43] Well, Sunnyside was initially established in 1875 by Edward Turner, and 12 months later, he was able to provide enough improvements to freehold the property. So the property was freehold in 1876. He passed the property on to his son in law, Henry Catermull, in 1900, and my grandfather and his brother Ben bought Sunnyside in 1922. So this October will have been here 100 years. And when my grandfather and Ben bought Sunnyside, some of the neighbours told them that there was a graveyard because they used to bring cane through this property to the juice mill that fronts Windermere Road and they’d see freshly dug graves. So I always knew where the graves were, but I was not able to heritage list the gravesite because I couldn’t prove it. But finally, after several failed attempts, I hit on the idea of getting ground penetrating radar and Gayle Read who then worked for the Bundaberg Council at the cemetery to bring it out. And she was able to substantiate the fact that 29 South Sea Islanders, one at least of whom is a child because of the size of the grave, are buried here and the depth of the graves is four foot, and they lie in three rows. And yes, it was very moving. And then what she did do was to mark out each grave. And so when she’d completed the exercise, you actually saw 29 marked graves on the ground with spray paint. And that was very, very moving. As a consequence of that and working with Matt Wordsworth from the ABC in Brisbane, the story went national and the Heritage Department finally decided to agree to heritage list the gravesite, as well as the two big weeping fig trees that you see here that were planted by Edward Turner in 1875. And as you’ve seen, I’ve fenced off the grave site. And I think that it’s important that we pay tribute to the people, we don’t know which islands they all came from, but that we pay tribute to them and we give them some dignity. And about six months after the grave site was Heritage listed, the South Sea Islander community in Bundaberg, under the leadership of Matt and his brother, who is now deceased, Matt Nagas organised a dedication ceremony and we had tribal chiefs from Vanuatu, a Christian minister of religion, and we also had the Prime Minister of the Solomon Islands at the time, Gordon Lilo, all came here for the dedication and I must say that the gravesites very peaceful and it’s part of our heritage now. And I’d like to think that if we were buried in a strange country, that someone would look after us. So it’s only fitting and proper that we do that. And there was only seven names registered as having died here on Sunnyside. And when I showed the names to Gordon Lilo, the Prime Minister of the Solomons at the time, he was able to show me by the names, where they came from. Three came from New Caledonia, two from the Solomon Islands and two from Vanuatu. So we know now that at least those three island nations have people buried here on Sunnyside.

Adele Bennett [00:05:37] So what was that ceremony like?

Brian Courtice [00:04:00] It was very moving. My wife and I stood back and just watched and it was done with dignity. They were probably only about 40 people here.

Adele Bennett [00:06:11] Why were they here to start with?

Brian Courtice [00:06:13] Well, the South Sea Islanders were brought in to Queensland from 1863 until 1904, basically as slaves to develop and work in the sugar industry. And while Britain had outlawed slavery by 1842 in the Caribbean. They turned a blind eye here to develop Queensland and there’s no doubt that it was the South Sea Island that established and developed sugar industry, hand in glove with the plantation owners. And there’s no doubt that when 62,000 were brought here and 16,000 died here, that they were treated very poorly. And court reports show that here on Sunnyside, that Edward Turner starved the South Sea Islanders, he belted them and he even assaulted a woman called Raincombe. So all in all, they were brought here as slaves. They were treated badly. And then as an act of as of Federation, the slavery had to end. So as a consequence of that, they phased it out over about six years. And so by 1906, South Sea Island labor ceased in the cane fields. But anyone who’s ever cut particularly green as I have, will tell you that it’s hard work. And when people have to work 12 hours a day, Monday to Friday and 10 hours a day on Saturdays, and are given starvation rations, it’ll kill you. And that’s what happened to so many men and women in the fields.

Adele Bennett [00:07:51] How is it here now, I know you mentioned a bit about the gravesite being peaceful, but can you describe it to people listening?

Brian Courtice [00:07:58] Well, at night time, when the when the moon comes through the trees, you see the moonlight on the graves. There’s no bad, eerie feeling at all. But we weren’t responsible for any of this. And yeah, it’s just peaceful. I guess that’s the only real word I can use. It’s peaceful. And I remember that a couple of weeks after the dedication ceremony, another tribal chief came from the Solomon Islands. And he sat here, where we’re sitting now on the veranda. And he looked at me and he said, I’d like to thank you for washing away the tears of shame from my eyes. And it was the words that Martin Luther King would have used. I was just blown away with it. That’s worth more than a million dollars to me, that respect and reaching out to someone from another country.

Adele Bennett [00:09:04] You mentioned a little bit before about Matthew Nagas. We’re going to have a chat with him as well on this podcast episode. Can you tell me a little bit more about his involvement and his connection to this place?

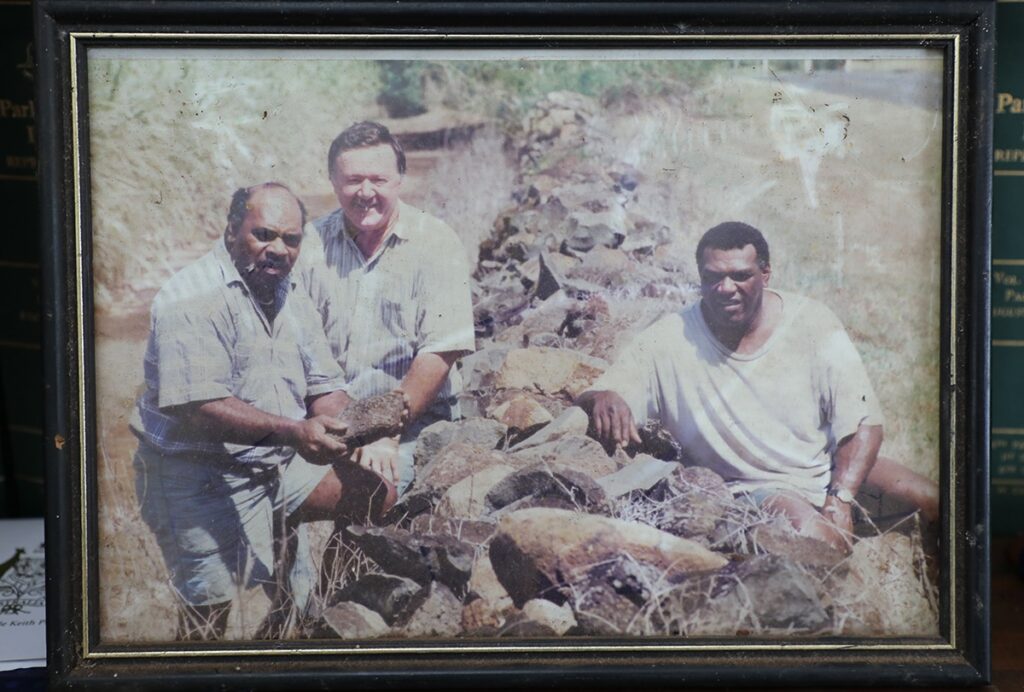

Brian Courtice [00:09:13] Well, Matt and I played football against each other, so it goes back over 50 years. And from when I first heritage listed the stone wall in 1996 up there, there was a photo which I’ll show you soon of Matt and I and his brother at the stone wall. And we’ve been in touch ever since on a regular basis. And he’s a is a real good bloke and a mate and I’m very proud to know him. The stonewall that that faces Windermere Road is, I think, only the one of two stone walls that are heritage listed in Queensland. The other ones at Mon Repos and it was, it was established by Edward Turner and the hard work of South Sea Islanders from 1875 until all the rocks were cleared basically. And it’s significant and it was easy to heritage list because it was tangible, it was visible. And that’s why the graves was so hard to prove, because I wouldn’t disturb the graves. And until I struck on the idea of ground radar, I wasn’t able to do it. So the stone wall was heritage listed in 1996, and the Graves sites are in 2013. So, you know, it’s the most that I can do to preserve our heritage, both my family’s heritage, but also the heritage of Queensland, by heritage listing the sites and those two big weeping fig trees were planted, as I mentioned, in 1875. And I asked a botanist how long do they live for? And she said, at least 500 years. So they’ll see me out.

Adele Bennett [00:11:09] Well, I guess on that, how important do you think it is that we sort of remember things, even terrible things that have happened in our past?

Brian Courtice [00:11:18] I think it’s absolutely vital. You can’t know yourself unless you know the history. It’s part of what happened and it’s not about persecuting anyone. The people that did the wrong thing have passed away well and truly. But it’s about making sure we never do it again. And I’ve always wondered why it’s not part of the school curriculum, because we should know our history. And in fact, the country that has done a good job with understanding their past is Germany. Germany acknowledges the past, acknowledges the years of darkness and comes through very well. So if we if we do understand history, I think that we’re better for it. And what was so appealing about the bipartisan debate yesterday in the state parliament was that people from all parties were supportive of recognition for the South Sea Islanders and all acknowledged what was done was wrong. And it’s only from that that you can improve things.

Adele Bennett [00:12:24] Last time I was here, you mentioned to me that you’ve got a family gravesite on the grounds as well. I just wanted to ask you, what was the decision to put your family in the ground here?

Brian Courtice [00:12:37] Well, Dad lived his whole life here, the 85 years of his life he lived here on Sunnyside. And I, probably what gave me the idea initially was when I went to Devon and I went to a little cemetery at Holwell. And saw my great, great, great grandfather’s grave under a big oak tree in a little country cemetery. And it struck me that that was symbolic. He was a Yeoman farmer. And I thought, that’s what I’d like to do here. So that’s what we’ve done. And I think that when you’ve had such a close association with property as we have, that that’s where I want to be laid to rest as well. And that’s why when I speak to people about the importance of the South Sea Island graves, it’s demonstrated by the fact that my family are buried in the same soil.

Adele Bennett [00:13:47] Well, thank you so much for joining me, and thank you for sharing your story.

Brian Courtice [00:13:51] Thank you.

Adele Bennett [00:13:52] So I’m joined by Matt Nagas on the phone. He’s calling from Townsville. Thanks so much for joining us on the podcast, Matt.

Matthew Nagas [00:14:00] Yeah, no problem.

Adele Bennett [00:14:01] As a third generation South Sea Islander, how did it feel for you when the graves were officially recognised at Brian’s place?

Matthew Nagas [00:14:09] Oh, a lot of that is like, what we say within our communities is that we have the stories, but the white community and farmers like Brian, they have the confirmation of our stories. So when we talk about our stories, where some of our people are just buried, where they were buried where they just dropped dead in cane paddocks. Brian’s discovery was confirmation of what, what we had be saying for years that our people weren’t taken to cemeteries, they were buried in the cane fields where they died. So that’s probably the first thing that come to mind. And then the other things that come to mind is and you know, they were very hard times. And during those hard times there’s a lot of death, you know, and their health wasn’t really good because they didn’t have good, stable diets and that type of thing. And they worked very hard. And in that, you know, some of the results are, the living conditions, all that sort of thing. Brian’s discovery of those grave sites was a confirmation from the stories that we passed down to our families and what’s been happening. But it’s a feeling of, well, it’s sadness because we know there was children that are buried there, too. So, you know, we don’t like to think too much why children passed away or even people that passed away at young ages, you know, they actually worked them into the ground. And it was a time of sadness back at time that we yeah, we get some recognition about what did happen to our people that helped establish the sugar industry that’s still viable today. The up and down with the sugar prices or whatever, that’s where the by-product of rum, that is, you know, a multi-billion dollar industry, you know, and our people helped establish that industry back in those days. And so and when I say lot of mixed emotions about that, it was not all for sad but happy times that we’ll get some recognition, our people will and those people that were buried there get some recognition that their labors weren’t in vain, that you know they, they give us a good lifestyle here in Australia, you know by their hard labors and it was a new way of life for a lot of us. We like the way of life here in Australia. So that’s why we’ve stayed on.

Adele Bennett [00:17:14] I saw when I was doing a bit of research online, a photo of you at the gravesites or just nearby sitting under the fig trees. Can you tell me how does it feel to visit a place like that where, you know, there was a lot of sadness?

Matthew Nagas [00:17:27] Yeah, we feel a lot of peacefulness, tranquility. And it’s really a place where we feel that we are very, feel at peace a lot. Sometimes we have another big burial site over where the South Sea Island complex is, and that is a very tranquil place to go to just to sit in them, you know, and just think about, you know, that the lives that those people, there’s over a thousand people buried at that particular site over there in adjacent to the cemetery. So Brian’s is sort of like the same sort of feeling of we were able to feel they will be paying some respects to them that where they were just laying there alone. We feel like that they’ve we’ve got somebody like ourselves now there to come and care for them. Brian does look after that, that particular area now, he doesn’t let any farming on it or that sort of thing, you know. And so we’re very thankful for that.

Gennavieve Lyons [00:18:47] Thanks for listening to the history of Sunnyside and the heritage listed South Sea Islander gravesite.

This episode wraps up our Hidden Histories series, I hope you’ve enjoyed learning more about the region’s past. Bye for now.