Time is ticking for Telstra's talking clock, with the countdown under way to close the information service on 30 September.

Most people aged over 40 will have called 1194 at some point. It was handy before mobile phones existed to check the time, especially around the start or finish of daylight saving, and after crossing time zones.

Bundaberg Regional Councillor Scott Rowleson alerted me to the Sydney Morning Herald report, which announced the news.

“It's the end of an era. I used to call this service as a kid and reset our house battery-operated clocks,” Scott said.

According to the report, Dennis Benjamin, executive chairman of Informatel which runs the number, says the “millisecond precise” service attracts about two million calls a year, and he wants it to continue.

However, a Telstra spokesman said the service was not compatible with its new network technology.

I haven't called 1194 for about 20 years and can't criticise Telstra for making a practical business decision, but agree with Scott it's the end of an era.

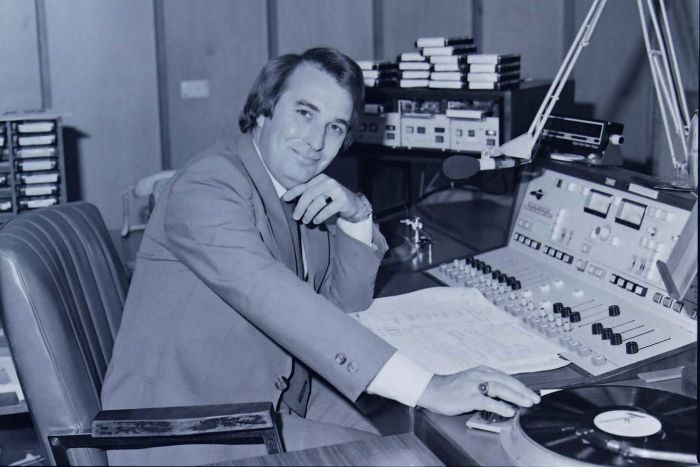

My personal interest in this is that I met the voice of the talking clock, Richard Peach, in the early 1990s when he became station manager of the ABC at Sale after a distinguished journalism career in Adelaide and Melbourne.

That was back in the day when radio presenters were celebrities.

Richard was a smooth operator, very affable, charming and by all accounts a great mentor for his staff.

I was a journalist at the Gippsland Times and contributed football news and livestock market reports to the ABC.

It was the era when ABC presenters had cultured accents, a sort of Oxford English that was similar to the BBC and before regional accents were allowed on the national broadcasters.

Richard's speech was impeccable. Sadly, after starting research for this piece I discovered he passed away in 2008, aged 59.

I recall that he used to drink white wine at the pub when everyone else was still drinking beer or Bundy and Coke.

Talking clock took 15 minutes to record

He told me the story once about how he recorded the talking clock. I don't remember the detail, but was surprised he said it only took a few minutes — 15 minutes according to Richard in the video below.

Apparently he recorded each number and the words: “At the third stroke it will be (insert numbers for hours and minutes) and (number) seconds (increments of 10).

Audio technicians must have then joined the words together to form repetitive phrases. This was before modern computers, so it was quite a feat.

Gordon Gow was the first voice of the talking clock when it became mechanised in 1953. Richard's voice took over in 1990.

Watch the video from 4:40 to hear his comments.

“It was fun and a little bit daunting, I could be here in 30 or 40 decades after I've waddled off,” he said (sadly not).

“I'm very honoured because it will be the most listened to voice in Australia which is why we had to get it right in the first place.

“It's a great responsibility and a lot of fun.”

Asked how long it took to record, Richard said: “We beat Gordon's record with the new technology we were able to use and got it down to a little under 15 minutes.

“It's not true they locked me away in a dark room for 24 hours to go right through the whole clock.”

Before Gordon Gow's mechanised talking clock in 1953, people wanting to know the precise time would dial a telephone exchange, and operators would read the time from the exchange clock.

The time was read live by changing shifts of women every 30 minutes. Their job was to mark off time in 30-second lots, speaking as soon as a light flashed.

“My heart would go out to them,” Richard said, “a bank of telephonists sitting there, staring at a clock, saying the same thing over and over again.

“At least I could use a machine to do that. What an awful job that must have been.

“Apparently it was so demanding on them they were only allowed to do it in shifts of one hour, then they had to go and have a break.”

The end of an era. Thank you Richard.